|

About Birth

Elective Induction of Labor

Table of Contents

“I live an hour from the hospital; if there’s a

blizzard, the road may be impassible.”

“I only get six weeks maternity leave. I don’t want

to get up from my desk to go to the hospital, but I don’t

want to sit home for two weeks either and only have four

weeks to recover.”

“My mother can come to help me out after the baby comes, but

she has to prearrange for the time.”

“If we induce labor, I can be sure of getting the doctor

that I really like.”

“I’m so huge and uncomfortable and tired of being pregnant.”

Who hasn’t heard one or more of these

nonmedical reasons for wanting to induce labor. Many

obstetricians have no objections to elective induction, and

some actually promote it: “We don’t want to let that baby

get too big” is probably the most common reason given,

although “impending post dates” gets my vote for most

creative indication. 36

The convenience of scheduling labor is even more of a boon

to busy obstetricians than to their patients, so if it

works and it’s harmless, why not induce?

To help your students make an informed decision, you must

have the facts about elective induction. Key, of

course, is whether it is generally safe and effective, but

in order to accurately weigh the risks and benefits, your

students will also need to know who makes a good candidate

and how to minimize the likelihood of problems.

Is

elective induction safe and effective?

The Food and Drug Administration and

the Physician’s Desk Reference, the bible of information on

drugs, recommend against elective inductions. 31, 35

The FDA “disallows” it; the PDR says,

“Since the available data are inadequate to evaluate the

benefits-to-risks considerations, Pitocin [the trade name

for oxytocin] is not indicated for elective induction of

labor.” By contrast, the American College of

Obstetricians (ACOG) includes “logistic factors” such as

“risk of rapid labor, distance from hospital, psychosocial

indications” on its list of indications for induction.

Inductions for these reasons would be elective inductions (ACOG

1999). 1

And, by ACOG’s lax standard, “tired of being pregnant” would

undoubtedly qualify as a “psychosocial indication.”

Problems with inductions stem from two

sources: the physiology of initiating labor and the side

effects of the procedures and drugs. First, despite

common belief that they can, obstetricians cannot switch

labor on at will. Starting and intensifying labor

involves a complex cascade of feedback mechanisms that

mutually reinforce and limit each other. It is an

elegant and delicate dance of hormones and other substances

between the baby, who initiates and controls the process,

and the mother. Dumping in oxytocin—with or without

cervical ripening procedures — often won’t initiate

progressive labor unless labor was on the verge of starting

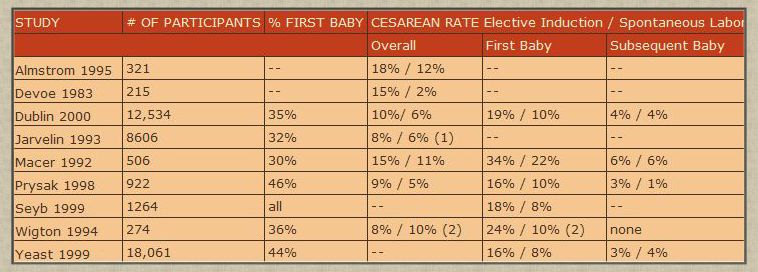

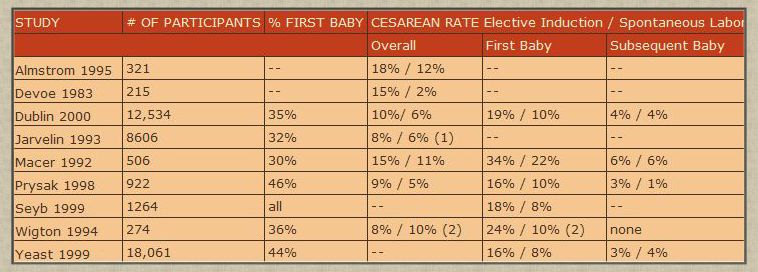

on its own. This is the main reason why studies

consistently show that inducing labor, apart from the reason

for induction, considerably increases the likelihood of

cesarean section in first-time mothers. 2, 8-9, 23, 28, 32, 36, 42, 45

(Some studies have concluded otherwise. The

reasons why are instructive and will be discussed in the

next section.) (See

Table.)

Second, all of the procedures and drugs used in inducing

labor can have adverse effects.

-

oxytocin (Pitocin, also called “Pit”):

-

uterine hyperstimulation:

Uterine hyperstimulation is a more common and serious

problem with inductions than when using oxytocin to

strengthen contractions in an already established

labor because it takes higher contraction pressures to

get and keep a labor going from a standing start.

20

Of ten studies comparing hyperstimulation rates at two

different oxytocin dosages, hyperstimulation rates

ranged from 2% to 60% at the lower oxytocin dose, and

six of the studies reported rates of 15% or more.

14

At the higher dose, hyperstimulation rates ranged

from 13% to 63%, and half reported that 25% or more of

the women experienced hyperstimulation.

-

fetal distress: Uterine

hyperstimulation can cause fetal distress.

Four studies reporting hyperstimulation rates also

reported fetal distress rates. 14

One reported an 8% rate at the lower dose; the rest

reported rates ranging from 15% to 54%.

-

low Apgar score: A separate

study reported that induction increased the percentage

of babies born in poor condition from 16% to 21%,

doubling the odds after statistical adjustment for

interdependent factors. 21

-

postpartum blood loss and

neonatal jaundice. 4-5, 7, 13, 16, 29, 37

Blood loss and jaundice may relate to direct effects

of oxytocin; increased use of IV fluids, especially IV

fluids that don’t contain salts; or both.

-

cesarean section: Oxytocin substantially increases

the likelihood of c-section in first-time mothers. (See

Table.)

-

procedures used with oxytocin:

Administering oxytocin requires an IV and electronic

fetal monitoring, which have their own potential adverse

effects. Because labor is more painful, women may

be more likely to want an epidural. One study comparing

first-time mothers having elective inductions with

first-time mothers beginning labor on their own reported

that having an epidural before 4 centimeters dilation

nearly quintupled the odds of cesarean, and they still

doubled with epidural placement at 5 centimeters or

more. 36

-

rupturing membranes:

Because amniotic fluid prevents umbilical cord

compression during contractions, rupturing membranes

increases the odds of episodes of abnormal fetal heart

rate and cesarean section for fetal distress. 12, 15, 28

This may be more of a problem during inductions because

contraction pressures are often higher. Since the

interval between rupture and birth may be long with an

induction, rupturing membranes increases the risk of

infection in women who subsequently have vaginal exams

and women colonized with group B strep. In rare

cases, it precipitates umbilical cord prolapse.

Cord prolapse is most likely when membranes are ruptured

early in labor when the head is still high, as would

happen with inductions.

-

prostaglandin E2 (trade

names: Prepidil, Cervidil): Prostaglandin E2, also

called dinoprostone, is inserted vaginally as a

gel (Prepidil) or as a removable tampon (Cervidil) to

soften the cervix. It can cause uterine

hyperstimulation and fetal distress. In some

cases, fetal distress can lead to cesarean section.

10

-

prostaglandin E1 (trade

name: Cytotec): Prostaglandin E1, more commonly

known as misoprostol is a tablet whose only FDA approved

use is as an oral medication for stomach ulcers. Its

manufacturer, Searle, does not formulate it for use in

labor and has repudiated its use for this purpose

because of safety concerns.33

The FDA says of Cytotec: 11

A major adverse effect of the obstetrical use of

Cytotec is hyperstimulation of the uterus which may

progress to uterine tetany [sustained contraction]

with marked impairment of uteroplacental blood flow,

uterine rupture (requiring surgical repair,

hysterectomy, and/or salpingo-oophorectomy [surgical

removal of ovaries and Fallopian tubes]), or amniotic

fluid embolism [very high maternal and fetal mortality

rate]. Pelvic pain, retained placenta, severe

genital bleeding, shock, fetal bradycardia

[dangerously slow fetal heart rate], and fetal and

maternal death have been reported. . . . The risk of

uterine rupture increases . . . with prior uterine

surgery, including Cesarean delivery.

Grand multiparity [several prior births] also appears

to be a risk factor for uterine rupture.

Unlike oxytocin, where the drip can be turned down or

off, Cytotec cannot be rescinded if it is causing

problems.

How did

obstetricians come to believe elective induction was

harmless?

-

belief that technology had

solved the problems with induction: The advent

of IV pumps to tightly control oxytocin dose and

prostaglandin gel to soften the cervix has led

obstetricians to believe that technology has conquered

the problems of uterine hyperstimulation and failed

induction. Obstetric philosophy and training

inculcates a preference for interventive management, so

once they stopped thinking that inducing labor had

serious consequences, induction rates were bound to

soar. In fact, hyperstimulation still frequently

occurs despite the pumps, and studies show that while

prostaglandin gel does an excellent job of softening the

cervix, it does little or nothing to reduce the cesarean

rate. 24, 30, 39

However, the preference for intervention and the belief

in its value blinds many obstetricians to those truths.

-

the norming of cesarean

section: The cesarean section rate has not been

below one woman in five since 1983. 40

After such an extended period, a rate in this range

feels normal, right, and unavoidable, although it is far

from that. If having many births end in c-section

isn’t seen as a problem, then the fact that inductions

lead to cesareans isn’t either.

-

the closure of the gap in

cesarean rates between induced and spontaneous labors:

The steep increase in cesarean rates has also

contributed to the illusion that induction no longer

matters. The gap between cesarean rates for

spontaneous and induced labors has closed because the

rate for spontaneous labors has risen to meet that of

induced labors. To illustrate, in a 1992 study,

researchers randomly assigned 3,400 women—two thirds of

them first-time mothers—to planned induction at 41 weeks

gestation or to await labor. 18

The women assigned to induction at 41 weeks were, in

effect, elective inductions since at the time, women

were not considered postdates until 42 weeks.

Twenty-one percent of the planned induction population

had cesareans versus 25% of the expectant management

group, leading the authors to conclude that planned

induction was the better policy. The study has

been cited since as an argument for elective

induction. But these were all healthy women with

full-term, singleton, head-down babies. In other words,

this was a population that should have been at minimal

risk for cesarean section.

A follow-up analysis reported

cesarean rates according to whether labor began

spontaneously or was induced. 19

Among first-time mothers, 26% of women beginning labor

spontaneously, whether in the planned induction or await

labor group, had cesareans. This rose to 30% of

women induced as planned and a whopping 42% of induced

women in the await labor group, of which only 17% were

done for abnormal fetal testing results. 18

By comparison, a study of 12,000 low-risk women

beginning labor at free-standing birth centers reported

a cesarean rate of 4% with 10% of first-time mothers

having cesareans. 34

-

bias toward intervention

over the natural process: The lead author of

the study above thinks that every woman should have a

cesarean as evidenced by her chairing a conference

entitled “Choosing Delivery by Caesarean: Has Its Time

Come?” 17

This goes a long way toward explaining why the main

paper misrepresents the true risks of induction and

ignores the appallingly high cesarean rates in both

spontaneous and induced labors.

The effect of obstetric bias can

also be seen in one of the studies in my table. Prysak

and Castronova compare outcomes in healthy mothers

having elective inductions matched to women beginning

labor spontaneously. 32

They conclude that elective induction is “safe and

efficacious” despite a cesarean rate of 16% for

first-time mothers having elective inductions versus 10%

for first-time mothers beginning labor on their own.

The authors favor elective induction as the following

passage from their introduction makes clear:

Advantages of elective induction include

patient-physician convenience, efficient use of

hospital personnel, and optimal time-of-day patient

care; unproved advantages include lowering the risk of

perinatal morbidity and mortality, birth trauma, and

cesarean delivery.

How did they make their data come out “right”?

They performed a logistic regression, a statistical

technique that accounts for confounding factors that may

obscure the true relationships among the issues of

interest. (An example of an appropriate use of logistic

regression would be accounting for other drug use and

cigarette smoking in cocaine users to get at the true

effect of cocaine on the baby.) Except that

Prysak and Castronova include the need for cervical

priming and the use of oxytocin in their regression,

which factored out the effect of induction on outcome.

Who

makes a good candidate for elective induction?

The ideal candidate for elective

induction is a woman who has given birth vaginally before,

whose cervix is ready for labor, and who has begun to

dilate. This, of course, is also a woman who will

almost certainly shortly go into labor on her own. In

descending order of probability of success would be a woman

with a prior vaginal birth or births whose cervix wasn’t

quite ready for labor, a first-time mother whose cervix was

ready to go, and a first-time mother with a long, firm,

closed cervix. A woman in the last category has truly

dismal chances for vaginal birth; as many as half of these

labors will end in cesarean section. 27

Perversely, though, if a woman’s doctor has a high cesarean

rate, inducing or awaiting spontaneous labor may not

matter. It will make no or only a small difference to

her chance of cesarean.

How can women considering elective induction minimize the

risks?

(adapted from The Thinking Woman’s Guide to a Better

Birth © 1999 by Henci Goer)

-

Refuse induction if you have

no prior births. Induction will increase the

chances of cesarean by anywhere from 50% to 250%. (See

Table.)

-

Refuse Cytotec (misoprostol,

prostaglandin E1). As noted above, Cytotec has a

propensity for precipitating women into short, violent

labors and a potential for catastrophic complications.

Cytotec was not formulated for use in inducing labor and

has not been approved by the FDA for this purpose,

although recently, lobbying by ACOG led the FDA to lift a

ban. Besides being riskier than Prepidil and Cervidil

(prostaglandin E2), Cytotec offers no compensating

advantages—at least not for women. Cytotec produces

virtually identical cesarean rates compared with

inductions involving prostaglandin E2. 22

The higher risks and equivalent effectiveness

notwithstanding, hospitals like Cytotec because it costs

mere pennies a dose compared with $75 to $100 dollars per

dose of prostaglandin E2. Obstetricians like it

because it allows them to practice “daylight

obstetrics”—insert the pill in the morning, return later

in the day for the delivery or the cesarean, be home in

time for dinner. 41

-

Refuse rupture of membranes before labor is

well-established and progressing. Having intact

membranes means you can back out if the induction doesn’t

work. Refusing early rupture also reduces the risk

of fetal distress from cord compression; the risk of

infection, which avoids IV antibiotics and septic workups;

and the rare but catastrophic risk of umbilical cord

prolapse.

-

Consider refusing induction

with an unready cervix and/or little or no dilation.

These conditions greatly increase the probability of

cesarean section regardless of the use of cervical

ripening procedures. 27, 43-44

-

When cervical ripening is necessary, request

Cervidil. Unlike Prepidil, it can be removed

should uterine hyperstimulation occur.

-

Avoid mechanical dilators for

cervical ripening. These materials gradually

dilate the cervix by absorbing water. They are not as

effective as prostaglandin E2 at either promoting

successful labor induction or achieving vaginal birth, and

they may increase the risk of infection. 25, 43 Again,

lower cost is the single advantage.

-

Although this should be

standard practice, make sure the IV fluid contains salts.

Salt-free fluids, especially in combination with oxytocin,

one of whose effects is fluid retention, can cause serious

blood-chemistry imbalances. 14

-

Have continuous electronic

fetal monitoring. It reduces the risk of

newborn seizures. 26

-

Insist on a low-dose(physiologic)

oxytocin regimen that allows at least 30 minutes between

dose increases. 14

The chance of developing adverse effects goes up with the

total amount of oxytocin given and the peak dose.

High-dose regimens greatly increase both.

-

Arrange to have the nurse try turning off the

oxytocin once active, progressive labor is established.

When labor kicks in, it may continue on its own without

the extra stimulus. This will be less painful for

you and easier on the baby. A plain IV will be kept

running, so oxytocin can easily be restarted if needed.

-

Low-dose, long-interval

protocols increase the odds of being able to turn the

oxytocin drip down or off in active labor.

3

-

Avoid or at least hold off on an epidural. Because

epidurals slow labor, they can substantially increase the

risk of cesarean section, especially when given early in

labor. Epidurals also cause fevers with prolonged

use. A fever in labor indicates a possible infection in

mother or baby and leads to a cascade of interventions.

-

Limit vaginal exams once

membranes are ruptured. There is a clear

relationship between length of time since rupture, the

number of vaginal exams, and infection. 38

-

Refuse internal

contraction-pressure monitoring. It

requires rupture of membranes, increases the odds of

infection, introduces risks of its own, and doesn’t

improve outcomes. 6

-

The discrepancy might have been greater had there been

more first-time mothers in the group.

-

10% is the primary cesarean rate at the study hospital

after removing cesareans for breech.

Bibliography

-

ACOG. Induction of labor. Practice Bulletin 1999, No

10.

-

Almstrom H, Granstrom L, and Ekman G. Serial antenatal

monitoring compared with labor induction in post-term

pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995;74:599-603.

-

Blakemore KJ et al. A prospective comparison of hourly

and quarter-hourly oxytocin dose increase intervals for the

induction of labor at term. Obstet Gynecol

1990;75(5):757-61.

-

Buchan PC. Pathogenesis of neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia

after induction of labor with oxytocin. Br Med J

1979;2:1255-7.

-

Chalmers I, Campbell H, and Turnbul AC. Use of oxytocin

and incidence of neonatal jaundice. Br Med J

1975;2:116-8.

-

Chia YT et al. Induction of Labour: does internal

tocography result in better obstetric outcome than external

tocography? Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 1993;33(2):159-61.

-

D’Souza SW et al. The effect of oxytocin in induced

labour on neonatal jaundice. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1979;86:133-8.

-

Devoe LD and Sholl JS. Postdates

pregnancy. Assessment of fetal risk and obstetric

management. J Reprod Med 1983;28(9):576-580.

-

Dublin S et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after

induction of labor without an identified indication. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:986-94.

-

Egarter CH, Husslein PW, and Rayburn WF. Uterine

hyperstimulation after low-dose prostaglandin E2

therapy: tocolytic treatment in 181 cases. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1990;163(3):794-6.

-

FDA. Cytotec 2002.

-

Garite TJ et al. The influence of elective amniotomy on

fetal heart rate patterns and the course of labor in term

patients: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1993;168(6 Pt 1):1827-1832.

-

Gilbert L, Porter W, and Brown VA. Postpartum

haemorrhage—a continuing problem. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1987;94:67-71.

-

Goer H. The Thinking Woman’s Guide to a Better

Birth. New York: Perigee Books, 1999.

-

Goffinet F et al. Early amniotomy increases the frequency

of fetal heart rate abnormalities. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1997;104(5):548-53.

-

Goldberg CC et al. Effect of intrapartum use of oxytocin

on estimated blood loss and hematocrit change at vaginal

delivery. Am J Perinatol 1996;13(6):373-6.

-

Hannah, M. Choosing Delivery by caesarean: Has its

time come? Sponsored by the University of Toronto’s

Maternal, Infant, and Reproductive Health Research Unit at

The Centre for Research in Women’s Health, Toronto,

Canada, Nov 7, 2002.

-

Hannah ME et al. Induction of labor as compared with

serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. A

randomized controlled trial. N Engl J Med

1992;326(24):1587-1592.

-

Hannah ME et al. Postterm pregnancy: putting the

merits of a policy of induction of labor into perspective.

Birth 1996;23(1):13-9.

-

Hauth JC et al. Uterine contraction pressures with

oxytocin induction/augmentation. Obstet Gynecol

1986;68(3):305-9.

-

Herbst A, Wolner-Hanssen P, and Ingemarsson I. Risk

factors for acidemia at birth. Obstet Gynecol

1997;90(1):125-30.

-

Hofmeyr GJ and Gulmezoglu AM. “Vaginal Misoprostol

for Cervical Ripening and Induction of Labour (Cochrane

Review).” In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2001.

Oxford: Update Software.

-

Jarvelin MR, Hartikainen-Sorri AL, and Rantakallio P.

Labour induction policy in hospitals of different levels of

specialisation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

1993;100(4):310-315.

-

Keirse MJNC. Prostaglandins in preinduction cervical

ripening. Meta-analysis of worldwide clinical experience. J

Reprod Med 1993;38(1 Suppl):89-100.

-

Krammer J et al. Pre-induction cervical ripening: a

randomized comparison of two methods. Obstet Gynecol

1995;85(4):614-8.

-

MacDonald D et al. The Dublin randomized controlled trial

of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1985;152(5):524-539.

-

Macer JA et al. Elective induction versus spontaneous

labor: a retrospective study of complications and

outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166(6 Pt 1):1690-1697.

-

Mercer BM et al. Early versus late amniotomy for labor

induction: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1995;173(4):1321-5.

-

Orhue AAE. A randomised trial of 45 minutes and 15

minutes incremental oxytocin infusion regimes for the

induction of labour in women of high parity. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol 1993;100:126-9.

-

Owen J et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of

prostaglandin E2 gel for cervical ripening and meta-analysis.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165(4 Pt 1):991-996.

-

Parke-Davis. Physician’s Desk Reference. 52d ed.

Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company, Inc., 1998.

-

Prysak M and Castronova FC. Elective induction versus

spontaneous labor: a case-control analysis of safety and

efficacy. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92(1):47-52.

-

Reuters Health. “Off-label Cytotec Use for Labor,

Abortion Prompts Searle Letter to Physicians.” Aug 29,

2000.

-

Rooks JP et al. Outcomes of care in birth

centers: the National Birth Center Study. N Engl J Med

1989;321(26):1804-1811.

-

Rooks JP. Midwifery and Childbirth in America.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997.

-

Seyb ST et al. Risk of cesarean delivery with elective

induction of labor at term in nulliparous women. Obstet

Gynecol 1999;94(4):600-7.

-

Singhi S et al. Iatrogenic neonatal and maternal

hyponatraemia following oxytocin and aqueous glucose infusion

during labor. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985;92:356-63.

-

Soper DE, Mayhall CG, and Dalton HP. Risk factors for

intraamniotic infection: a prospective epidemiologic

study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161(3):562-6.

-

Trofatter KF. Endocervical prostaglandin E2 gel for

preinduction cervical ripening. Clinical trial results.

J Reprod Med 1993;38(1 Suppl):78-82.

-

United States 1996. Month Vital Stat Rep 1997;46(1 Suppl

2).

-

vigilante obstetrics. Presented at Celebrating the Gift

of Birth, sponsored by the International Cesarean Awareness

Network, Cleveland, OH, Apr 20-22, 2001.

-

Wigton TR and Wolk BM. Elective and routine induction of

labor. A retrospective analysis of 274 cases. J Reprod Med

1994;39(1):21-26.

-

Williams MC, Krammer J, and O’Brien WF. The value

of the cervical score in predicting successful outcome of

labor induction. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90(5):784-9.

-

Xenakis EM et al. Induction of labor in the

nineties: conquering the unfavorable cervix. Obstet

Gynecol 1997;90(2):235-9.

-

Yeast JD, Jones A, and Poskin M. Induction of labor and

the relationship to cesarean delivery: a review of 7001

consecutive inductions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180(3 Pt

1):628-33.

© 2002

by

Henci Goer

article

reprinted with permission

Henci

Goer is an award-winning American author and internationally-know

who writes about pregnancy and childbirth from an evidence-based

perspective. She is the author of The Thinking Woman's Guide to a

Better Birth. Her previous book, Obstetric Myths Versus Research

Realities, is a highly-acclaimed resource for childbirth

professionals. An independent scholar, she is an acknowledged expert

on evidence-based maternity care. Goer has written consumer

education pamphlets and numerous articles for magazines as diverse

as Reader's Digest and the Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal

Nursing.

|