|

About Birth

TACTILE AND

EMOTIONAL SUPPORT DURING LABOR: THE DOULA

Johnson

& Johnson

Photos courtesy of Charis Doulas

"Doula"

is a Greek word meaning "a woman who helps other women." In the

realm of contemporary perinatal care, the term has come to mean a

caregiver who provides continuous physical, emotional and

educational support to the mother before, during and just after

childbirth. Doulas stay with the mother throughout labor, constantly

assessing and responding to her needs.

A doula is a layperson, most often a woman, who understands the

biological and medical processes involved in labor and obstetrics,

and who usually has assisted in at least five or six deliveries

under the supervision of another doula. Her training also provides

her with knowledge of obstetrical interventions, so that she can

explain them to the woman and her partner in the event they are

needed.

Doulas typically function as a part of the "birthing team," serving

as an adjunct to the midwife or the hospital obstetrical staff. Physicians and labor and delivery nurses may appreciate the doula's

sustained attention to the mother, especially in hospitals where

demands on the staff interfere with exclusive contact with the

mother. The doula also serves a critical role in supporting and

educating the woman's partner, enabling him or her to be as involved

and as effective as possible in supporting the mother.

In the United States, most doulas work as independent providers

hired by the expectant woman. (In fact, many hold full-time jobs

outside the realm of health care.) Increasingly, managed care

organizations are offering doula support as part of regular

obstetrical care. In some European institutions, doula support is

offered as a standard of care by midwives or nursing students. In many cultures, of

course, the practice of a knowledgeable woman helping a mother in

labor is not labeled anything as official as "doula" support; it is

simply an ingrained, centuries-old custom.

Overall, the defining characteristic of doula-type care is

continuous, uninterrupted, emotional and physical support of the

woman for the duration of the labor and childbirth. -21

THE ROLE OF TOUCH IN

DOULA CARE

The doula can use many kinds of touch and massage, depending on what

the mother finds helpful. Doulas may, for example, gently touch or

stroke the mother's shoulder, hand or foot while offering

reassurance. They regularly confirm what type of touch and body

positions the mother is finding most beneficial, and alter their

touch as needed. The doula can use many kinds of touch and massage, depending on what

the mother finds helpful. Doulas may, for example, gently touch or

stroke the mother's shoulder, hand or foot while offering

reassurance. They regularly confirm what type of touch and body

positions the mother is finding most beneficial, and alter their

touch as needed.

As labor progresses, the doula may cradle the woman in her arms,

wipe her brow, massage her and use other forms of touch as she

educates her about what is happening to her body and in the birth of

her child. She often instructs the partner or birth companion in

doing the same, helping him or her to soothe the mother. Together,

the doula and the partner may physically support the laboring mother

in walking, sitting, leaning or squatting. To relieve back labor,

the doula might use back rubs, hot cloths and pressure.

Studies have documented that a doula's touch and support leads to

reduced pain-or, at the very least, the mother's perception of

reduced pain. Controlled comparisons of women who received doula

support with those who did not revealed that mothers in the "doula

groups" reported significantly less labor pain. 22

The doula provides support after birth as well. Among other things,

she may facilitate the parents' bonding with the child by

encouraging close contact from the moment of birth, especially in

the first hour.

CLINICAL BENEFITS OF

DOULA SUPPORT

Within the past decade, a number of controlled studies have

supported the use of doulas. Among these studies, two conducted in

Guatemala City and one in Houston, Texas are of particular

interest. -23, -24, -25 In all three, the investigators randomly assigned

first-time mothers to doula support or no doula support. In

comparisons between the doula and no-doula groups, the data were

adjusted for interventions such as oxytocin and C-sections, making

the presence or absence of a doula the only major difference in the

labor environments of these two groups. Within the past decade, a number of controlled studies have

supported the use of doulas. Among these studies, two conducted in

Guatemala City and one in Houston, Texas are of particular

interest. -23, -24, -25 In all three, the investigators randomly assigned

first-time mothers to doula support or no doula support. In

comparisons between the doula and no-doula groups, the data were

adjusted for interventions such as oxytocin and C-sections, making

the presence or absence of a doula the only major difference in the

labor environments of these two groups.

PICTURE

The defining characteristic of doula care is continuous,

uninterrupted emotional and physical support of the woman throughout

labor and childbirth.

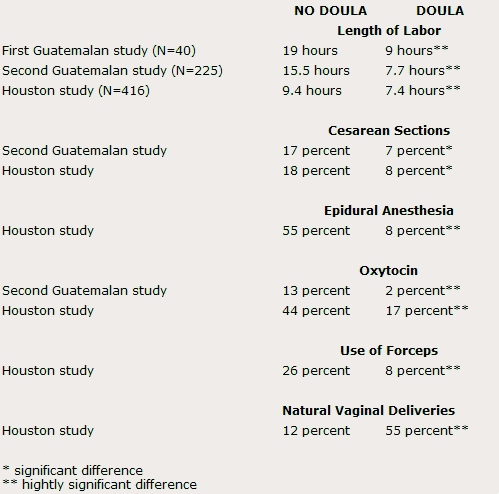

Data from those studies, which demonstrate the benefits of doula

support, are described below and summarized in Table 1 -22

Length of Labor. The studies showed that doula support

reduced labor time. Researchers were able to conclude that in spite

of obstetrical methods of inducing and speeding up labor (e.g.,

artificial rupture of membranes, augmentation of contractions, forcep deliveries, C-sections), the mothers who received doula

support were the ones with the shortest labors.

Vaginal Deliveries vs. C-sections. By conservative estimates,

cesarean sections are performed in about 20 to 25 percent of U.S.

births each year. In contrast, C-section rates among doula-assisted

groups in these studies were lower: seven to eight percent.

Table 1.

Need for interventions in births without and with doulas -22

Epidural Anesthesia. In the Houston study, more than half of

the women without a doula requested or required epidural

anesthesia-compared with only eight percent in the doula group.

Oxytocin. In one Guatemalan study, only two percent of women

who had a doula required oxytocin, a drug that increases the

strength of contractions; 13 percent in the control group needed the

drug. The Houston study documented significantly larger percentages

in both groups. While oxytocin is helpful to some mothers, it causes

contractions to become more forceful and painful-leading some women

to need an epidural or other pain medication as a result of the

oxytocin's effects.

Forceps. Although physicians use forceps much less often

today than in the past two decades, this tool is still helpful in

some deliveries, especially when epidurals have been administered.

The studies document forceps deliveries eight percent for

doula-supported births, compared with 26 percent in the control

group, a difference largely due to the more frequent use of epidural

anesthesia in the no-doula groups.

Natural Deliveries. In the Houston study, 55 percent of the

doula-supported women had natural vaginal deliveries-that is,

delivery without C-section, anesthesia, oxytocin, medication or

forceps-whereas only 12 percent of the women without doulas

delivered naturally. In the words of the authors, "it is fascinating

to reflect that the presence of one caring woman throughout labor

resulted in such a large difference." -22

INSTITUTIONALIZED USE

OF DOULAS: A CLINICAL MODEL

About 25 years ago, the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin,

Ireland, introduced continuous emotional support on its labor and

delivery units, in addition to a strict definition of the onset of

labor. The results were impressive and so beneficial that the

hospital established doula-type care - delivered by nurse-midwifery

students - as a mainstay of its maternity services for all patients. Key results of this labor-support program include:

1. a

drop in the hospital's average length of labor to between a half to

a third of what it had been before the program. Since the late

1980s, the mean length of labor for first-time mothers at the

hospital has been slightly less than six hours. (The program also

uses membrane rupture and oxytocin to assure a certain dilation

rate.);

2. a C-section rate of five to six percent that has been sustained

for two decades; -22 and

3. a significantly increased patient census, facilitated in large

part by the shorter labors, lack of complications and more rapid

patient discharge following most of the births. -21

BEYOND LABOR: BENEFITS

TO MOTHER AND BABY AFTER BIRTH

The benefits of doula support do not end in the delivery room.

Rather, benefits have been evident in both mother and infants long

after the birth and the doula's support.

Mothers' first 24 hours. In the Guatemalan study, the

researchers observed the women in the doula and no-doula groups

through a one-way mirror for the first 25 minutes after the mothers

left the delivery rooms. The ratings showed that the doula-supported

mothers had more affectionate interaction with their infants,

smiling, stroking and talking to their newborns more than did the

no-doula mothers. -22

In addition, studies in Johannesburg, South Africa looked at 189

first-time mothers who had an untrained laywoman supporting them

throughout labor. These female caregivers constantly used touch and

verbal encouragement to comfort and reassure the women. -26, -27

The new mothers who received doula care:

1. reported less pain during childbirth at the one-day postpartum

interview than they expected, while the control group mothers

reported more discomfort; and

2. reported less anxiety at 24 hours and 6 weeks postpartum (even

though the groups had similar levels of anxiety before labor), had a

better perception of how they had coped with the birth experience,

and spent more time with their babies after birth.

The newborn at six weeks. Positive effects of doula support

on the infant were also evident weeks after the doula's involvement

was over.

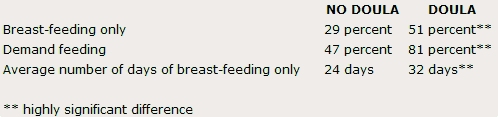

Infant feeding. In the Johannesburg study, the doula-supported group

showed a significantly higher incidence of breast-feeding and

"on-demand" feeding. Also, 63 percent of the no-doula group

experienced feeding problems with the newborn, while only 16 percent

of the doula group experienced problems. -22

Table 2.

Feeding behavior at six weeks with and without doulas - 22

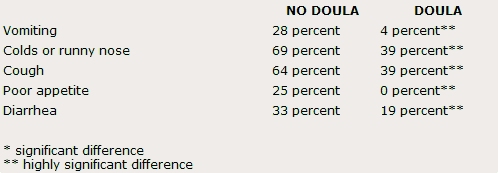

Infant health. Although the infants had been similar in

all respects at birth, mothers in the two groups from the

Johannesburg study reported marked differences in the health of

their babies at six weeks. The research did not determine whether

these were perceptual or actual differences, but doula care during

labor and delivery clearly instilled some attitudinal or physical

advantages to mother or child, or both. Some of the differences may

be related to the higher incidence of breast-feeding in the doula

group.22

Table 3.

Infant health problems at six weeks after birth with and without

doulas - 22

Mother-infant bonding. Mothers in the doula group reported

spending 1.7 hours a week away from their babies, as opposed to 6.6

hours reported by the no-doula group. The doula-group mothers

reported an average of 2.9 days to develop a relationship with the

baby, compared to 9.8 days for the other group of mothers. The

results suggest that mothers in the doula group were more available

and better able to form an attachment with their newborns. -22

Mothers' emotional state. Psychological tests in the

Johannesburg study found significantly less anxiety, fewer signs of

depression and a higher level of self-esteem in the doula-group

mothers, suggesting that, among other things, they are less likely

to suffer postpartum depression. Mothers who feel better about

themselves are also more likely to provide a nurturing environment

for their infants.

Researchers also reported that doula-supported mothers felt a great

increase in satisfaction with their partner after the birth of the

baby. Mothers who did not receive doula support did not express this

degree of satisfaction. In a variety of areas, the doula-supported

mothers' perceptions of themselves, their babies and their partners

were clearly more favorable. -22

MECHANISM OF ACTION:

WHY DOES DOULA SUPPORT WORK?

The mechanism of action by which doula care produces its positive

effects is unknown but is assumed to involve the combined influences

of the doula's physical and psychological interventions.

Some investigators theorize that the catecholamine stress hormones

adrenalin and noradrenalin cause the labor of many mothers to slow

down, making complications more likely and the labor experience more

taxing and stressful. By calming the patient through touch,

reassurance and relaxation, however, the doula may alleviate the

woman's fear and apprehension and, in turn, help to moderate the

hormonally mediated stress reactions, ultimately lessening the need

for medical intervention and shortening the labor.

IMPLICATIONS FOR

HEALTHCARE COSTS

When Klaus et al. conducted a meta-analysis of six randomized doula

studies, they reached the conclusion that the presence of a doula

reduces the overall cesarean rate by 50 percent, length of labor by

25 percent, oxytocin use by 40 percent, pain medication by 30

percent, the need for forceps by 40 percent, and request for

epidurals by 60 percent.

These results indicate the potential financial benefits of doula

services, on both institutional and national levels. If widespread

use of doula services were to cut the number of cesarean sections in

the U.S. by half and reduce epidural use as well, savings in the

nation's medical-care costs would be an estimated $1.3-1.6 billion

annually. -21

REFERENCE

1.

Spitz RA. Anaclitic depression. Psychoanalytic Study of the

Child.1946;2:313-347.

2.

Suomi SJ, Brown CC et al. The role of touch in rhesus monkey social

development. In The Many Facets of Touch, Johnson & Johnson

Pediatric Roundtable. 1984;10:41-56.

3.

Suomi SJ. Interview, 1994.

4.

Seay BM, Harlow HF. Maternal separation in the rhesus monkey.

Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 1965;140:434-441.

5.

Seay BM, Hansen EW, and Harlow HE Mother-infant separation in

monkeys. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1962;3:123-132.

6.

Bowlby J. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969.

7.

Harlow HE The heterosexual affectional system in monkeys. American

Psychologist. 1962b;17:1-9.

8.

Goy RW, Wallen K, and Goldfoot DA. Social factors affecting the

development of mounting behavior in male rhesus monkeys. In

Reproductive Behavior, Montagna W and Sadler W, eds. New York:

Plenum Press; 1974.

9.

Suomi SJ. Genetic and maternal contributions to individual

differences in rhesus monkey biobehavioral development. In Perinatal

Development: A Psychobiological Perspective, Krasnegor N et al.,

eds. New York: Academic Press; 1987:397-420.

10.

Fairbanks LA. Early experience and cross-generational continuity of

mother-infant contact in vervet monkeys. Developmental

Psychobiology. 1989;27:669-681.

11.

Suomi SJ. Primate separation models of affective disorders. In

Neurobiology of Learning, Emotion and Affect, Madden H, ed. New

York: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1991 :195-214.

12.

Schanberg S, and Field T. Maternal deprivation and supplemental

stimulation. In Stress and Coping Across Development, Field T,

McCabe P, and Schneiderman N, eds. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

13.

Higley JD, Suomi SJ, and Linnoila M. A longitudinal assessment of

CSF monoamine metabolite and plasma cortisol concentrations in young

rhesus monkeys. Biological Psychiatry. 1992;32:127-145.

14.

Schanberg S et al. Maternal deprivation and growth suppression. In

Advances in Touch, Johnson & Johnson Pediatric Roundtable,

Gunzenhauser N, ed. 1989;14:3-10.

15.

Meaney MJ, Aitken DH, Bodnoff SR, Iny U, and Sapolsky RM. The effect

of postnatal handling on the development of the glucocorticoid

receptor systems and stress recovery in the rat. Progress in

Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 1985;7:731-734.

16.

Reite M. Effects of touch on the immune system. In Advances in

Touch, Johnson & Johnson Pediatric Roundtable, Gunzenhauser N, ed.

1989;14:22-31.

17.

Laudenslager M, Reite M, and Held P. Early mother-infant separation

experiences impair the primary but not the secondary antibody

response to a novel antigen in young pigtail monkeys. Psychosomatic

Medicine. 1986;48:304.

18.

Coe CL, Lubach G, Ershler WB, and Klopp RG. Influence of early

rearing on lymphocyte proliferation response in juvenile monkeys.

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1989;3:47-60.

19.

Laudenslager ML, Rasmussen KLR, Berman CM, Suomi SJ, and Berger CB.

Specific antibody levels in free-ranging rhesus monkeys:

relationships to plasma hormones, cardiac parameters, and early

behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;26:407-420.

20.

Suomi SJ. Touch and the immune system in rhesus monkeys. In Touch in

Early Development, Field TM, ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Assoc.; (in press).

21.

Klaus MH. Interview, 1994.

22.

Klaus MH, Kennell, JH and Klaus, PH. Mothering the Mother. Reading,

Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1993.

23.

Sosa R, Kennell JH, Robertson S, and Urrutia J. The effect of a

supportive companion on perinatal problems, length of labor and

mother-infant interaction. New England Journal of Medicine.

1980;303:597-600.

24.

Klaus MH, Kennell JH, Robertson SS, and Sosa R. Effects of social

support during parturition on maternal and infant morbidity. BMJ.

1986;293:585-587.

25.

Kennell JH, Klaus MH, McGrath SK, Robertson SS, and Hinkley CW.

Continuous emotional support during labor in a U.S. hospital.

Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265:2197-2201.

26.

Hofmeyer GJ, Nikodem VC, and Wolman WL. Companionship to modify the

clinical birth environment: effects on progress and perceptions of

labour and breast feeding. British Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynecology. 1991;98:756-764.

27.

Wolman WL. Social support during childbirth: psychological and

physiological outcomes. Masters' thesis. University of

Witwatersrand, Johannesburg; 1991.

28.

Field TM, et al. Tactile/kinesthetic stimulation effects on preterm

neonates. Pediatrics. 1986;77:654-658.

29.

Acolet D, et al. Changes in plasma cortisol and catecholamine

concentrations in response to massage in preterm infants. Archives

of Disease in Childhood. 1993;68:29-31.

30.

Solkoff N and Matuszak D. Tactile stimulation and behavioral

development among low-birthweight infants. Child Psychiatry and

Human Development. 1975;6:33-37.

31.

White J and Labarba R. The effects of tactile and kinesthetic

stimulation on neonatal development in the premature infant.

Developmental Psychobiology. 1976;6:569-577.

32.

Ottenbacher KJ, Muller L, Brandt D, Heintzelman A, Hojem P. and

Sharpe P. The effectiveness of tactile stimulation as a form of

early intervention: a quantitative evaluation. Journal of

Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1987;8:68-76.

33.

Field TM. Interview, 1994.

34.

Field TM, et al. Massage therapy for infants of depressed mothers.

Miami, Florida: Touch Research Institute, University of Miami School

of Medicine; 1994.

35.

Klaus MH and Klaus PH. The Amazing Newborn. Reading, Massachusetts:

Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1985.

36.

Kuhn C, Schanberg S, Field T, Symanski R, Zimmerman E, Soafidi F,

and Roberts J. Tactile/kinesthetic stimulation effects on

sympathetic and adrenocortical function in preterm infants. Journal

of Pediatrics. 1991;119:434-440.

37.

Current Touch Research Institute Studies (listing available from

Touch Research Institute, University of Miami School of Medicine).

38.

Preliminary data: TRI Massage Studies (information available from

Touch Research Institute, University of Miami School of Medicine).

39.

Lester BM, Boukydis CFZ, Garcia-Coil CT, and Hole WT. Colic for

developmentalists. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:4,321-333.

40.

Liepack S, et al. Infant colic: a review. (Unpublished manuscript.)

Miami, Florida: Touch Research Institute, University of Miami School

of Medicine.

41.

Massage effects on asthmatic children. (Unpublished manuscript.)

Miami, Florida: Touch Research Institute, University of Miami School

of Medicine.

42.

Wheeden A, et al. Massage effects on cocaine-exposed preterm

neonates. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

1994:14, 318-322.

43.

Field TM. Infant massage. In Zero to Three. Bulletin of the National

Center for Clinical Infant Programs; 1993;14(2):8-12.

44.

Field TM, et al. Massage reduces anxiety in child and adolescent

psychiatric patients. J. Am Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1992;31

(1):125-131.

45.

Scholz K, Samuels C. Neonatal bathing and massage intervention with

fathers, behavioral effects 12 weeks after birth of the first baby:

The Sunraysia Australia Intervention Project. Int'l. J. of Behavior

Development. 1992;1~5:67-81.

46.

Righard L, Alade MO. Effects of delivery room routines on success of

first breast-feed. Lancet. 1990;77(5):1105-1107.

47.

Klaus MH, Kennell JH et al. Human maternal behavior at the first

contact with her young. Pediatrics. 1970;46:187-192.

48.

Kaitz M, Lapidot P, Bonner R, and Eidelman A. Parturient women can

recognize their infants by touch. Developmental Psychology.

1992;28:35-39.

49.

Kaitz M, et al. Fathers can also recognize their infants by touch.

(Unpublished manuscript.) Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department

of Psychology; 1992.

This

monograph for healthcare professionals is provided to you by

Johnson & Johnson

Touch In Labor and Infancy

'Behold, I will bring them from the north country, And gather them

from the ends of the earth,

Among them the blind and the lame,

The woman with child and The one who labors with child, together,

A

great throng shall return there...And My people shall be satisfied with My goodness, says the LORD.'

Jeremiah 31:8, 14~~~

©2009 Charis Childbirth

Services, All Rights Reserved

Feel free to forward this newsletter to friends in its entirety,

leaving all attribution intact.

May 2010

|